Evidence Based Investing vs Index Funds

Index Funds

In the early 70’s, the first index funds were formed to offer investors a better choice than what active mutual funds offered (stock picking, market timing, track record investing). As the name implies, an index fund buys and holds the securities tracked by a particular index, which seeks to reflect the performance of a particular asset class. The earliest index funds tracked the S&P 500 index (500 largest US company stocks). Over time, additional index funds, including similar ETF’s (exchange traded funds), have expanded to track a host of other indices, representing a wide range of asset classes.

Advantages of Index funds

Index funds provide investors tighter controls over 3 critical areas:

- Asset Allocation. How you allocate your portfolio across various market assets classes plays a significant role (91.5%*) in your long term performance.

- Global Diversification. Through broad and deep diversification, the sum of your whole risk can be lower than its individual parts.

- Costs-The most efficient way to increase returns is to lower expenses. Index funds are far cheaper than actively managed asset classes.

Weaknesses of Index Investing

- Index Dependency. Although most index funds are cheaper to manage than active strategies, they are restricted to hold equities according to the index they track. When an index “reconstitutes” what underlying stocks make up an index, funds that track that index must buy and sell specific holdings to match the index, and quickly. Given the market knows which stocks they need to buy and sell, and the fact they need to do this transaction quickly, index fund must pay what the market will offer. This classic supply and demand pricing results in a “buy high, sell low” environment. This is called the reconstitution effect. A study conducted in 2009 on the Russell 2000 index showed that the spread between additions and deletions was more than 20%. This was for one day of trading during the reconstitution period.

- Compromised Composition. An index represents an accurate proxy of the asset class it is targeting. However, evidence has shown that smaller stocks pay a premium over larger stocks, as well as distressed stocks over non-distressed. This is true even within specific asset classes. An index fund typically is more concerned with aligning itself with a specific index than it is with capturing a larger more accurate representation of the asset class being targeted.

- Trading Costs. Because an index must align itself with its targeted asset class, trades have to be continually made to keep in line with the constitution of that particular index.

- Lack of Control in Downward Markets. Changes to an index occur once a year when the index is “reconstituted”, determining the specific securities and their relative weighting in the makeup of that specific index. Unfortunately, the market doesn’t wait for the “reconstitution”, and at times can be very volatile. This can cause big problems for indexes as they have to ride out these swings until “reconstitution” of the index occurs. This was seen in the latest crash of 2008. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were extremely large and were part of specific indexes’ prior to the crash. However, as they became somewhat insolvent, the index had to continue to hold the security all the way down until they would be adjusted out at “reconstitution”.

- Lack of Depth and Broad Diversification. Because so much money is required to duplicate foreign indexes, and the liquidity involved is much higher, ETF’s cannot get access to the dimensions of returns from small and micro-cap asset classes. It cannot be done with an ETF or Index. This causes a big problem in creating a broadly diversified portfolio, especially since these categories have been shown to offer higher returns over a long period of time. They also serve as great diversifiers to other more traditional asset classes because of their low correlation.

Evidence Based Investing

The evidence is compelling that investors have higher expected returns when they reject actively managed funds and invest in a globally diversified portfolio of low management fee index funds, in an asset allocation appropriate for them. That said, academically minded innovators from around the world discovered ways to improve on an index’s best traits and eliminate their weaknesses. These are referred to as passive asset class funds or structured asset class funds. Rather than chasing returns through stock picking and market timing, passive asset class managers seek to capture risk dimensions identified through academic research. Unlike a pure indexing approach, an asset class strategy allows a flexible portfolio composition and gives traders more freedom to pursue value in the transaction process. This can result in lower costs, more precise asset class exposure, and enhanced returns. The result is a tax efficient, structurally engineered portfolio.

Advantages of Evidence Based Investing

- Index Independence. Evidence based fund managers passively track and index but have established their own parameters for cost effectively investing in the lion’s share of the securities within the asset class being targeted. They are not restricted to buying a particular security at a specific time and avoid the added expense caused during reconstitution.

- Flexibility when to buy and sell stocks. An index fund buys and sells stocks as they enter and leave the index. A structured asset class manager has the ability to reduce turnover and increase tax efficiency by establishing a range that permits them to hold a stock even if it drops out of the index.

- Flexibility in Stock Selection. Evidence based mangers can establish a screen to exclude categories of stocks with historically poor returns, like IPO’s (initial public offering stocks), securities in financial difficulty, securities in bankruptcy, merger or involved in corporate action. Index fund managers do not have this flexibility. This was displayed during the crash in 2008 (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac).

- Improved Concentration. Evidence based managers can more aggressively pursue targeted risk factors which historically yield higher returns. Asset class mangers have more flexibility to hold a greater concentration of smaller and value stocks within a specific asset class than does an index fund.

- Use of Block Trading Techniques. There are sophisticated trading techniques a small cap, structured asset class manager can use that are not available for index fund managers. Since the market for these securities are relatively small, dumping a large block can affect the stock price. A structured asset class fund may be able to buy these stocks at a favorable price from a seller who has an urgent need to liquidate holdings.

- Tax Efficiency. Although index funds are tax efficient, structured asset class funds can engage in additional strategies that can make them even more efficient.

- Avoiding intentional short-term gains

- Selling stocks with bid losses and tax harvesting those losses

- Avoiding the purchase of stocks just before their ex-dividend date.

- Can focus on minimizing dividends in an effort to improve after tax returns.

Weaknesses of Evidence Based Investing

There is nothing exciting about investing in a prudent manner. There is very little to get the blood rushing or the excitement of guessing right on a particular stock. Its basis is founded in evidence and long term probabilities rather than a feeling or thought of predicting what will happen over a short period.

The Greatest Factor in determining your performance

Investor Behavior!!!!

The greatest factor in determining how your investment will perform has nothing to do with market factors. How your react to the market has everything to do with what you can expect to receive. All the evidence in the world will have no effect on your outcome if you don’t adhere to it. Discipline is the key, and without the knowledge of how and where true alpha (return) comes from, you don’t stand a chance.

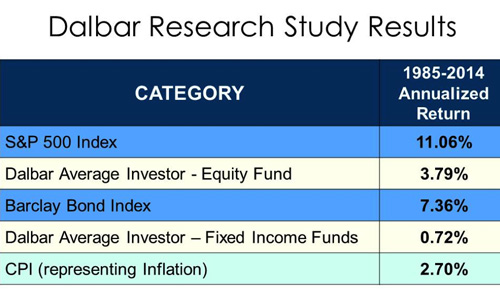

Dalbar, Inc. is a leading financial services research firm that has conducted multiple studies with regard to investor behavior. Their most significant finding in this study is that regardless of how well a particular investment may perform, the average investor is unlikely to realize the same return. For example, while the S&P 500 earned 11.06% from 1985-2014, the average equity fund investor realized and annualized return of 3.79%. One contributing cause for this result is that the average investor’s holding period for a fund was only 3.33 years. Investors were chasing market returns by selling when a fund dropped in value and buying when funds were on the way up. Therefore, they missed the long-term gains inherent in the fund. In the end, the crucial point to remember is that an investor’s performance does not equal the investment’s performance. Chances are you will underperform the market, not beat it.

The chart below clearly indicates that DALBAR Average Equity Investor returns have been significantly less than the leading equity market index.

The indices referenced above are described more fully in the endnotes. This chart is for illustrative purposes only. Indices are unmanaged, cannot be invested in directly and their returns do not represent the performance of any actual fund or transactions and do not include management fees, transaction costs or expenses. In its 2014 Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior, Dalbar defines “Average Investor” as “The universe of all mutual fund investors whose actions and financial results are restated to represent a single investor. This approach allows the entire universe of mutual fund investors to be used as the statistical sample, ensuring ultimate reliability.” p. 22. “Average equity investor”, as used in the same study, is that subset investing only in equity mutual funds. See p. 28 at n. 4. Dalbar’s average investor equity fund returns are set forth in a table on p.5. Past performance is no guarantee of future success.

Investment returns in and of themselves are somewhat irrelevant. The object of all long-term investors should be to optimize after-tax, real (inflation-adjusted) returns. Increasing one’s purchasing power is what truly matters, not a specific percentage return on your money. Despite the average investor UNDER PERFORMING the index by 7.27% over a 30 yr. period, investors only increased their purchasing power by only 1.09%, and that number likely turns negative on an after taxes basis.

So much of investing is counter intuitive to the human mind and thought process. We have all been conditioned to a certain degree to either seek pleasure (performance return) or avoid pain (reduce risk). The emotion behind these variables leads investors to make poor decisions at the wrong times. The following are but a few examples of how we become our own worst enemies:

Investors own Worst Enemies

Fear of Regret

This deals with the emotional reaction people experience after realizing they’ve made and error in judgment. Faced with the prospect of selling a stock, investors become emotionally affected by the price at which they purchased the stock. So, they avoid selling it as a way to avoid the regret of having made a bad investment or admitting they were wrong. No one likes being wrong, and fewer will admit to it.

Some investors avoid this regret (fear) by following the conventional wisdom and buying only what everyone else is buying, rationalizing their decision with “everyone else is doing it”. Oddly enough, many people feel much less embarrassed about losing money on a popular stock that most of the world owns than about losing on a stock that is unknown or unpopular.

Mental Compartments

Humans have a tendency to place particular events into mental compartments. The difference between these compartments sometimes impacts our behavior more than the event itself.

For example, you plan on going to the movies, and tickets are $20each. When you get there you realize you’ve lost a $20 bill. Do you still go to the movie? Studies show that approximately 88% of people would. Now, let’s say you purchased the tickets in advance. When you arrive at the theater, you realize you left the ticket at home. Would you pay $20 for another ticket? Only 40% would under this scenario. In both scenarios, it would cost you $40 to see the movie. But the reaction because of different mental compartments is dramatically different.

In investing, this is seen by the hesitation to sell and investment that once had monstrous gains and now has a modest gain. People get accustomed to the higher gains. They create mental compartments for the higher number, causing them to wait for the return to get back to where it once was.

Pain of Risk (Loss) / Pleasure of Return (Gain)

Individuals are more satisfied avoiding losses than they are with receiving equal gains. A loss appears larger than a gain of equal size. This explains why investors hold onto losing stocks, hoping the price will bounce back and avoid losses. Investors often make the mistake of chasing market action by investing in stocks or funds that attract the most attention. Research shows that money flows into high performance mutual funds more rapidly than money flows out from funds that are underperforming.

Anchoring

Investors tend to place too much credibility in recent market views, opinions, and events, and ignoring historical long-term averages and probabilities. Investment decisions are often influenced by price anchors deemed important because of their relevance to recent prices. This makes the more distant returns of the past irrelevant in the investor’s decisions.

Investors get optimistic when the market goes up, assuming it will continue to do so. Conversely, investors become extremely pessimistic during downturns. Anchoring (placing too much importance on recent events and ignoring historical data) causes an over or under reaction to market events which results in prices rising too much on good news and falling too much on bad news.

At the peak of Optimism, greed takes over and stocks move beyond their intrinsic value. A great example of this was during the dot com era. When did it become a rational decision to invest in stock with no earnings? Conversely, market panics and crashes had investors selling stock for a fraction of its book or asset value.

Overconfidence

People generally rate themselves as being above average in their abilities. They also overestimate the depth of their knowledge and their knowledge relative to others. Many investors (including professional advisors or fund managers) believe they can consistently time the market. In reality, there is overwhelming evidence that proves that it can’t be done consistently over a long period of time. Such overconfidence results in excess trades, with trading costs depleting profits.

That said, investors can be their own worst enemies. Trying to out-guess the market doesn’t pay off over the long term. In fact, it often results in bizarre, irrational behavior, not to mention a heavy toll on your wealth. Thus, the role emotion plays in the success of an investment strategy cannot be over emphasized.

Implementing a strategy that is well thought out, supported by academic research, and can eliminate irrational human behavior will likely result in returns that few will achieve. A process that reduces risk and enhances returns, while lowering cost, will go a long way toward reaching ones financial goals. Discipline is the key, and knowing how and why you invest in what you invest in will keep you disciplined.

Counterintuitive

So much of investing is counterintuitive to human thought and emotion. The concept of buy low and sell high seems so basic and easy. However, putting it in practice is extremely hard to do as our minds are conditioned to think otherwise. In what other area of life are we asked to buy or do more of something that is presently not working? Where else are we asked to stop doing what is giving us results we are pleased with? This is what occurs in a buy low, sell high scenario. In addition to our own mind fighting against us, Wall Street and the various marketers manipulate and exaggerate the problem. They spend billions of dollars a year advertising fear of loss or promising riches (greed) to cause us to act in a way that creates profits to their bottom line. They even do this while giving the appearance they are working in our best interest.

A simple example is in the administration of 401Ks or even individual investment accounts. During a review, the broker will explain that they are going to remove the funds that are not performing well and replace them with ones that have shown to be better performers. On the surface, it sounds reasonable and that they are acting in your best interest. It may even align with what you would do, or what feels like is the right course of action to take. However, what they are doing, as a practice in managing your money, is buying high and selling low. Weather this is done out of ignorance (bad training), or on purpose, the results are disastrous to the investor. Yet, this is done day after day, year after year, and no one seems to see a problem with this.

Misleading or Misunderstood Information

Unfortunately, not all of what we read or hear is presented in a way that speaks to an investor’s language. If we read that a Mutual Fund has had an average return of 12% over the last 10yrs, we would expect that a $10,000 initial investment would grow to just over $31,078 at the end of the 10th year. However, the personal rate of return you get form a financial services provider like Fidelity and Schwab can be very different. Most Fund companies measure their returns based on a Time Weighted Rate of Return. What our mind thinks of is a Dollar Weighted Rate of Return. The differences can be substantial, and can lead investors to much disappointment and confusion.

Let’s put these in an example. Say you had $10,000 at the beginning of the year and your investments did great in the first 3 months. Your $10,000 turned into $12,000 without you adding a penny. Now on April 1, you put in $20,000 more, but your investments stalled in the rest of the year, and you end the year with $32,000. So you made 20% on $10,000 in the first 3 months and you made 0% on $32,000 in the next 9 months. If you plug in these values in a spreadsheet and use the XIRR function, you get 8%.

If you didn’t put in additional $20,000 on April 1, your return would’ve been 20%. That’s how your investment choices did and that’s how Fidelity or Schwab will report to you. There’s a big difference between the 8% Dollar Weighted Rate of Return and the 20% Time Weighted Rate of Return because the cash flow in this example is unusually large. If we change the additional contribution on April 1 from $20,000 to $1,000 and have the end of year value at $13,000 instead of $32,000, the two returns would be much closer. The Dollar Weighted Rate of Return would be 18.6%, and the Time Weighted Rate of Return would still be 20%.

There have been many funds that have shown double digit positive returns over extended periods whose dollar weighted averages have been negative. You can see form the example above that the differences can be dramatic between what a Fund shows as their rate of return and what the actual investor receives.

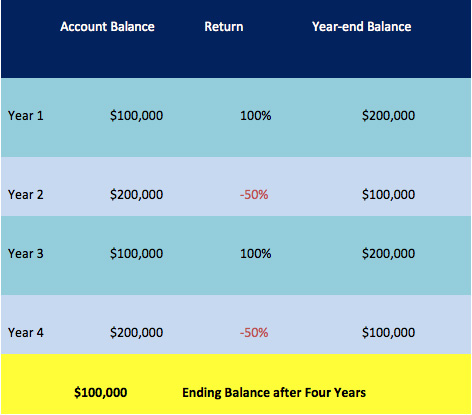

Another area of misconception is: Average Rate of Return and Actual Rate of Return. The mind hears one thing but thinks another. The following example, shows that what we are told is not always what we receive. Despite an Average Rate of Return of 25% over 4yrs, our Actual Rate of Return could be 0%.

Average Return Vs. Actual Return

(Traditional Investing)

Average Return = 25%

Actual Return = 0%

Although this chart is somewhat of an exaggeration, it emphasizes the point that what is stated is not necessarily the same thing as you are thinking. Unfortunately the language used by the industry does not always mean what we think it does. It’s no wonder the investor gets confused, frustrated, and easily swayed year after year form one fund or strategy to another, only to find themselves falling further away from where they want to be. Decisions based upon the wrong assumption are a roadmap to failure. That’s where education and coaching come into the picture, and takes a prominent role in allowing investors to make prudent decisions with their money.

Summary

Successful investing is simple, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. It’s good to remember that the future is always uncertain, so it is always a difficult time to invest. By having a strategy, sticking to it, and knowing your circle of competence, you can overcome the top investing mistake everyone makes-and profit when other people succumb to it.